Winter 1620

But it pleased God to vissite us then, with death dayly, and with so generall a disease, that the living were scarce able to burie the dead…But that which was most sadd & lamentable was, that in 2. or 3. moneths time halfe of their company dyed, espetialy in Jan: & February, being ye depth of winter, and wanting houses & other comforts; being infected with ye scurvie & other diseases, which this long vioage & their inacomodate condition had brought upon them; so as ther dyed some times 2. or 3. of a day, in ye foresaid time; that of 100. & odd persons, scarce 50. remained.

—William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

Shortly before the Mayflower reached Cape Cod in November of 1620, Richard More turned 6 years old. In early December, his older brother by one year Jasper More aged 7, assigned to the care of Governor John Carver and his wife Katherine, succumbed to illness and died onboard. He was buried in the dunes nearby, one of the many early, unmarked graves.

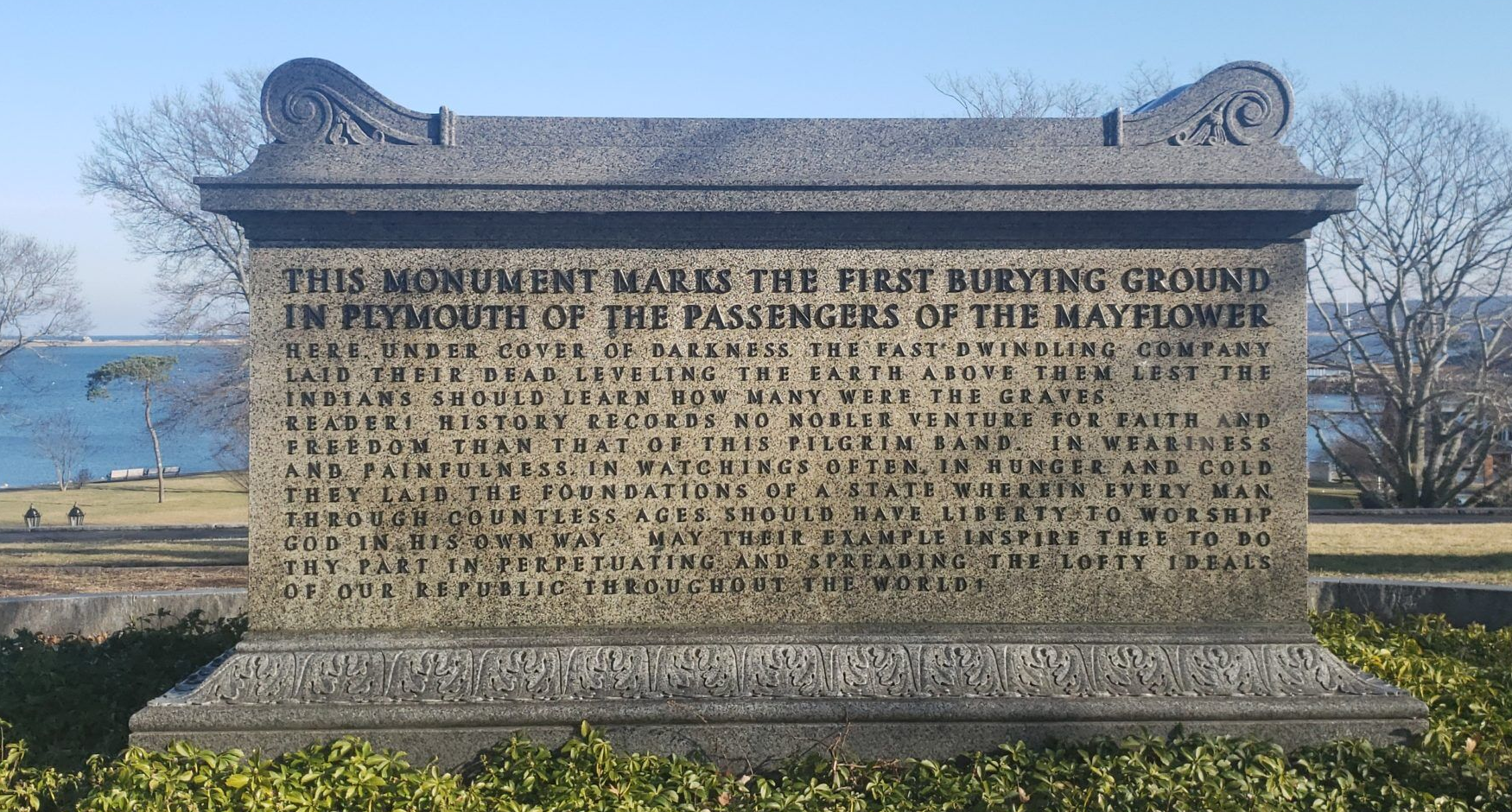

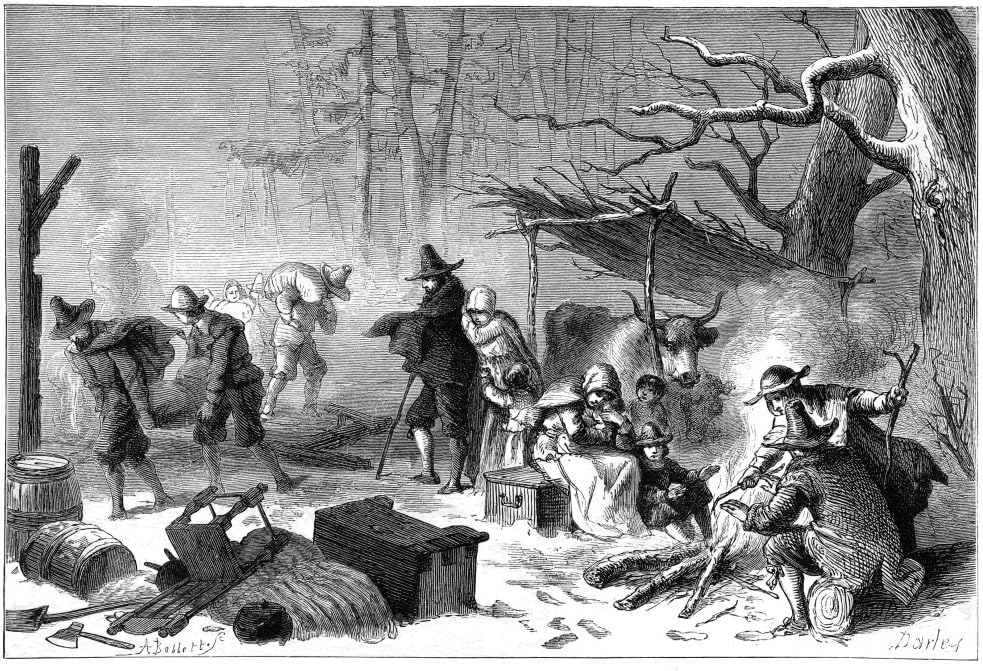

Work began late around December 23rd 1620 to build a common shelter. Between January and March of 1621, sickness quickly swept through the half-built settlement during the harsh winter. William Bradford in Of Plymouth Plantation describes how eventually up to 3 people began to die each day. Soon one right after another, first Ellen More age 9, placed in the household of Edward Winslow, died early in that first sickness; then even the youngest, Mary age 3, indentured along with Richard to the family of William Brewster, also perished. Both were buried at Coles Hill, the colony’s makeshift burial ground where graves were deliberately left unmarked and disguised to conceal the heavy losses from any watching indigenous groups. Soon the ship became a death house, as Richard would have even had to assist in carrying the bodies of his siblings and others ashore. By April of 1621, of the original 102 Mayflower passengers only 55 remained alive.

Richard More was the sole surviving member of his family in the New World.

Over the next several years, Richard More grew from a small orphaned boy into a young member of the colony. As a servant to the Brewster family, he was to bow his head when spoken to, his work typically involved fetching water, gathering firewood and helping prepare meals. He was allowed to eat only after the family had finished, as he sat on a stool nearby and at night slept on a straw matt on the floor. In 1942 a metal spoon was found with the initials RM carved into it near where the Plymouth barricades stood. This was the probable physical object which fed and kept Richard More alive. The events of Plymouth’s survival he would soon experience growing up, had to have made a lasting impression.

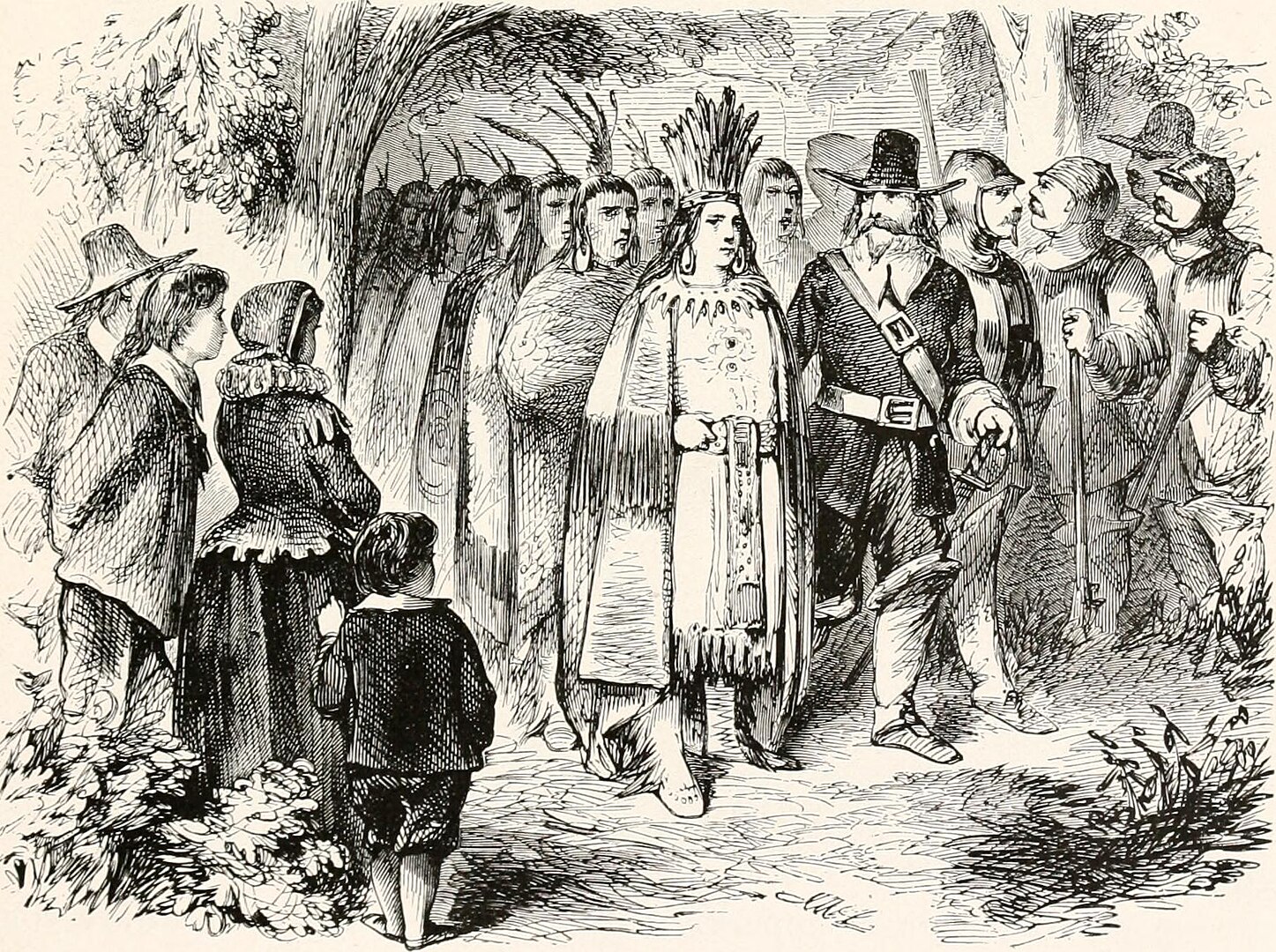

The first formal contact between the Pilgrims and the Indigenous peoples of New England occurred on March 16, 1621, when Samoset, an Abenaki sagamore, walked into Plymouth Colony and astonished the settlers by greeting them in English to famously ask if they had any beer?

His arrival opened a crucial line of communication, and within days he returned with Squanto (Tisquantum), He and William Bradford developed a close friendship, who considered him “a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. Who directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities and never left them till he died.”

By late 1621 an additional ship named the Fortune arrived unexpectedly at Plymouth, bringing new settlers but almost no provisions. While increasing the colony’s population placing additional strain on already limited supplies and heightened the settlement’s dependence on stable relations with the native tribes led by chief Massasoit.

Unlike the Pilgrims, the young male passengers of The Fortune were not there for religious reasons but rather profit, as they soon attempted a separate English settlement at Wessagusset which almost immediately began to collapse. Poor planning, hunger, and a lack of discipline led many of its settlers to steal food from neighboring Native groups, severely damaging relations. Tensions escalated as local tribes around Wessagusset, already frustrated by the colonists conduct, began considering violent retaliation, threatening both that settlement and Plymouth by association.

In early 1623, Massasoit fell gravely ill, and Edward Winslow traveled to his village to tend to him. After recovering, Massasoit revealed that some Massachusetts area leaders were secretly plotting an attack on the English. Angered by the behavior of Wessagusset colonists and emboldened by their vulnerability, local tribes were planning a coordinated attack. Plymouth, as their ally, was also a target.

Around the same time, soon after completing construction of an 8ft barricade wall. Plymouth received alarming news of the 1622 Virginia massacre, in which 347 colonists had been killed by the Powhatan Confederacy in less than 2 hours. The combination of Massasoit’s warning and the reports from Virginia convinced Plymouth’s leadership that preemptive action was necessary to prevent a similar catastrophe.

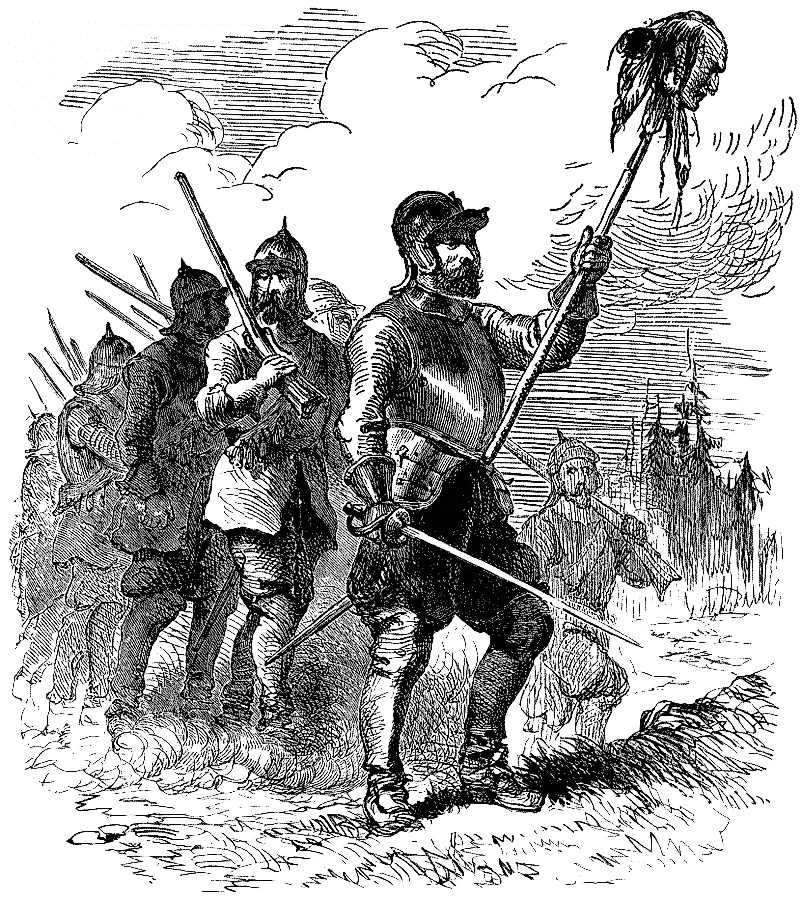

Acting on this belief, Captain Myles Standish led a small force to Wessagusset to neutralize the perceived threat. Confrontations quickly escalated, culminating in Standish killing the warrior Wituwamat, a figure identified as one of the conspirators. Standish had Wituwamat decapitated, bringing the head back to Plymouth as visible proof that the danger had been eliminated.

Though the operation relieved the immediate threat to the colony, it also caused long-term strain with several indigenous groups who viewed the act as excessive and dishonorable, marking a turning point in the increasingly fragile peace that had characterized the Pilgrims’ earliest years in New England.

In 1627, when Plymouth conducted its famous Cattle Division—a repartitioning of the colony’s livestock among its households, Richard More now age 13 was recorded as still alive and among the family of William Brewster. This census reflects a turning point: the colony was stabilizing, surviving, and distributing resources. For Richard, it symbolized the transition from a precarious orphan to a recognized member of a functioning community.

The fift lot fell to Mr Willm Brewster & his companie Joyned to him

To this lot ffell one of the fower Heyfers Came in the Jacob Caled the Blind Heyfer & two shee goats.

Love Brewster

Wrestling Brewster

Richard More

Henri Samson

Johnathan Brewster

Lucrecia Brewster

Willm Brewster

Mary Brewster

Thomas Prince

Pacience Prince

Rebecka Prince

Humillyty Cooper

In 1628 Richard entered an apprenticeship with Isaac Allerton, one of the most influential, if controversial figures in early Plymouth. Allerton was deeply involved in trade and was frequently absent from Plymouth as he pursued economic opportunities across New England and the broader northern Atlantic. His time under Allerton marked Richard’s shift from indentured child servant to his adult career as a well regarded sea captain.

By 1633 Allerton’s trade network extended north to Machias Maine where French commander Charles de La Tour killed some of his men and took others for ransom to Port Royal. In 1654 at age 40, the now Captain Richard More participated in the Siege of Port Royal when the French fort “was reduced to English obedience”. Not far from where over a century later his great granddaughter and my ancestor Susanna Knowlton along with her husband Captain Josiah Dodge in 1761 would relocate to Upper Granville Nova Scotia from Wenham Massachusetts during the Planter Migration. Their descendants would remain in the Annapolis region for over another century (with perhaps some still there even to this day), before eventually returning to Lynn Massachusetts where Richard More’s sixth great granddaughter and my grandmother Dorothy May Dodge would be born in the early 20th Century.